By Jordan Ross

In his book chapter “Before the Image, Before Time” (2003), Georges Didi-Huberman contends that “the history of images is a history of objects that are temporally impure, complex, overdetermined.”[i] Artworks for Didi-Huberman are anachronistic, and art history often misses temporal differentiations for the sake of classification and order. When artworks fail to be neatly sorted within a certain style or epoch, they take on a dangerous plasticity. They are incongruous, evading the traditional conventions of their time. This difference and unverifiability tears the veil of censorship, allowing the emergence of a new object to behold.[ii] French philosopher Catherine Malabou has used the concept of plasticity to explain how certain experiences trigger a process of destruction within our brains, causing a shift in our identity and a taking on of new form.[iii] Malabou considers these intense encounters as moments of explosive plasticity, an event that can result in the sculpting of new identity. I argue art is one possible site for this moment of explosive plasticity that triggers metamorphosis within its viewer, a shaping of identity through the plasticity of the brain and its apprehension of external stimuli. Dangerous art: that is, art that is temporally, visually, or experientially plastic, creates a momentary site of destruction within our brains that forces us to adapt to the new information or sensory data we have received. Enacting their plasticity, our brains are moulded by these sites of destruction, causing a shift or transformation of identity. Cassils and Patricia Piccinini are two artists that successfully exemplify this process, embodying both a performance of explosive plasticity whilst simultaneously creating a site for destruction within the viewer. For Malabou, these destructive sites are paramount to the evolution of our society as they open the pathways for renewal and transformation. If we recognise that our identities are not as rigid as they may seem, it becomes more probable that we will recognise how the oppressive structures that govern us are also capable of change and transformation.

Didi-Huberman explains that the art-historian’s process is built upon purification and simplification, a “denial of the flesh of things.”[iv] It is a condition of blindness, we often view the artwork not to explore its complexities but to situate it within a chronology and movement. Yet, images have more memory and future than those who contemplate them.[v] For it is the image that will remain after we are long gone, we are the transient and fragile object before the image which holds an element of permanence. This is why Didi-Huberman labels art as dangerous, as their fundamental plasticity threatens our need for everything to be in its place.[vi] Inadvertently, this reminds us of our own plasticity. Like the artwork, we are shaped by our time, memory and history, and have the potential to take on new forms.

The concept of plasticity first appeared in Goethe’s work on aesthetics and education under the term Plastizität, “the capacity to be sculpted.”[vii] This referred not only to the sculpting of artworks, but also to the construction of knowledge and personality within the subject. Yet, Catherine Malabou argues we are completely ignorant of this dynamic. We believe our brains to be rigid and entirely genetically determined, when in actuality they are plastic, caught within a process of unending sculpting.[viii] As plastic, we are caught between the sensible and annihilation. Through receiving form and the creation of new form, the ‘original model’ of ourselves is “progressively erased.”[ix] We are consistently born out of our own destruction. While the word destruction has negative connotations, in this sense, it is not always the case. For example, we may view an artwork that challenges or contradicts a part of ourselves, forcing us to fashion a new aspect of ourselves out of the rupture that has been created. For Malabou, destruction is always followed by a regeneration and reformation of the self. It is a metamorphosis as opposed to resurrection, a “tentative effort to bridge the gap that opened at the core of identity.”[x] This is perhaps why we are ignorant to the plastic nature of our brain, these instances of metamorphosis are rapid, often taking place without our intervention or knowing.

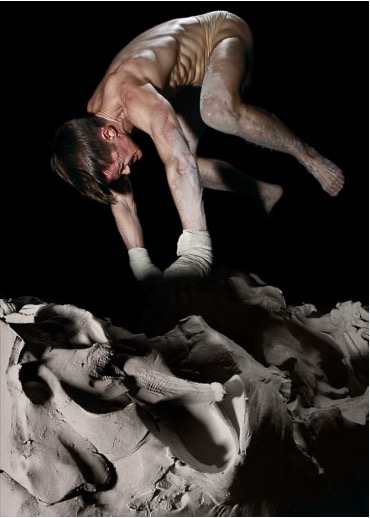

I believe a great metaphor for this is found in Cassils Becoming an Image (2012) (Figure. 1).

Figure 1. Cassils, Becoming an Image (2012), performance, ONE Archives, Los Angeles.

In this performance piece, the audience is placed in a completely dark room while Cassils ferociously pummels a two thousand pound block of clay. The room is only lit up in fleeting moments by the flash of a photographer, burning the image of Cassils’ violent display onto their retinas. This performance encapsulates the explosive and destructive nature of plasticity, with the sudden and aggressive punches into the clay by Cassils slowly sculpting it. A destructive counterpart is fundamental in all of creation, we all experience cellular annihilation. We would not have fingers if a separation between them did not form.[xi] We can imagine each of Cassils’ punches to be the instances of destruction and the clay as our brain adapting and taking a new form. This imposition of new form over the old occurs without mediation, sometimes unnoticed, just as the viewer in this performance struggles to see what is taking place. The performance is multiplicitous in the way it displays the process of transformation, while also triggering a process of transformation within the viewer.

As others have described, this performance piece is as much about death and destruction as it is the creation of life.[xii] Cassils chose the material of clay because it is “formed through acts of violence.”[xiii] These overt acts of violence are no stranger to queer people, and given that Cassils is a transgender artist, we could view the end result of Becoming an Image (2012) as a monument to queer oppression. Queer people are often forced to adapt and reconstruct themselves to remain safe in hostile environments, with their way of being shaped by the acts of violence enacted upon them. Thus, the brain can be formed, but also deformed, by experience and culture.[xiv]

However, Cassils’ work also displays the positive nature of plasticity that is inherent to the formation of queer identity. Clay can be considered a ‘trans object’ as it shares the trans bodies characteristics of “malleability, fluidity, and the ability to shape-shift while remaining the same substance.”[xv] In Cassils’ work, even though the clay is brutalised and the form is completely changed by the end of the performance, it is still the same substance. Cassils often displays the end result of these performances as part of their exhibitions, for instance Clay Bash (2012) at Ronald Feldman Fine Arts Gallery. From the relentless beatings they endure, the clay sculptures are malformed and stray far from their initial smooth, symmetrical shape. It follows then, that we are all the same substance, and all have the capacity to shift, change, and present ourselves in a way that is radically different from cis/heterocentric modes of being. Malabou argues that the reason why the structures in place are often unforgivably rigid is because we are ignorant to our innate plasticity.[xvi] One could argue that queer people are fundamentally more conscious of this, as for many gender non-conforming people their mere existence disproves a concrete and rigid binary gender structure that is void of evolution or growth.

The brain then, as shown in Cassils performance, is our own form of personal artwork, it is shaped by our experience and culture.[xvii] Organic matter can be moulded, changed and reappropriated just as clay or marble is. The work of Patricia Piccinini, particularly Teenage Metamorphosis (2017) (Figure 2), also highlights this process of plasticity while simultaneously creating a site of destruction within the viewer through the use of abjection.

Figure 2. Patricia Piccinini, Teenage Metamorphosis (2017), silicone, fibreglass, human hair, found objects, Queensland Art Gallery.

In this artwork, a pig/human hybrid rests on a beach towel, accompanied by a book and a stereo. The hybrid creature bears an uncanny human resemblance. We recognise and are drawn to the human features of the eyes, mouth, nose and hair. The creature is mutated; folds of skin converse and overlap, and growths erupt from its spine and patches of hair protrude from irregular locations of the body. Piccinini declared that her work has an “emotional dimension that shifts the apparent rational implications.”[xviii] No matter how offensive the creature may be to our eye, an empathetic connection is created through human-like qualities and scenery. This is a situation we can all recognise, and the title of the work and the size of the creature allow us to recollect our own teenage years. The creature appears pudgy, with large amounts of excess skin, mirroring the malleability and plasticity of our identity. We can imagine that this creature will grow with time into something else, but now it is curled up in an infantile manner, awaiting metamorphosis, the loose skin slowly being filled with new form. Malabou states that “we must all of us recognise that we might, one day, become someone else, an absolute other.”[xix] This artwork by Piccinini shows a subject in metamorphosis and portrays the othering of oneself post-reorganisation. The humanity of the creature is only subtly recognisable, mimicking plasticity and how the former versions of ourselves are progressively erased as we continue to change.[xx]

Piccinini’s work personifies our plasticity, yet also has the capacity to create a site of destruction within the viewer, as many artworks do. In this case, it is Piccinini’s use of abjection that has a destructive element to it. The abject refers to the unclean or unordered. We abject any type of filth, whether it be excrement, vomit, sickness, waste, and so on, as it reminds us of our immanence.[xxi] It threatens the breakdown of the reality we have constructed and the self.[xxii] Therefore, abjection allows us to build ourselves upon what we are not. In Teenage Metamorphosis (2017), the line between the supposed concrete subject and the helplessness of pre-signification are blurred. The creature is both unknowable in its bizarre appearance and familiar in its human-like qualities. Here, the abject cannot be “radically excluded from the place of the living subject”, it is intertwined with subjectivity as we are forced to face our plasticity and immanence.[xxiii] Piccinini’s artwork is then what Malabou would refer to as a site of destruction. The giving and receiving of form between the artwork and the subject cause an ‘explosion’ within the self, a change in the “neuronal connections that impacts the construction of personality.”[xxiv] In the creature, what we have abjected from ourselves returns to us once more, instantaneously shattering our conceptions of the self and imposing a reconstitution of knowledge and personality to take place.

For Malabou, these moments of destruction and the realisation of our plastic nature are necessary to dismantle capitalism and the patriarchy.[xxv] Malabou asks: “why, given that the brain is plastic, free, are we still always and everywhere in chains?”[xxvi] Therefore, we must awaken to the nature of our own plasticity to change the future. If we are not rigid, neither are the oppressive structures that bind and control us. The ignorance of our innate condition to evolve and change is part of what stunts the evolution of society. Though people in power may prefer that this feigned concept of rigidity persists, we can already see in the multiplicity of queer identities unfolding in contemporary society that these inhibiting boundaries are beginning to unravel.

It is true that our brains can be changed by trauma, as shown in Cassils work, but it can also be changed by seemingly anodyne events, like viewing Piccinini’s work in a gallery. Thus, I believe that art is an important part of a culture and community that seeks to evolve. As Didi-Huberman shows, art takes on a dangerous plasticity, it can be incongruous and temporally impure. This impurity and resistance toward rigid classification is what makes art the perfect site for the awakening to the plasticity of the self. As seen in Becoming an Image (2012) by Cassils, there are already artworks that allude to plasticity and how we are moulded by experience over time. It reminds us that just as we create and sculpt artworks, we can sculpt ourselves and consequently sculpt the reality in which we live. Patricia Piccinini’s work shows us how this might take place, in her case, creating artworks that generate empathy and force us to reconfigure what it means to be human. While the experiences that shape us may make us all appear different, we are all bound by an innate freedom that plasticity reminds us we have. To recognise this is one way to subvert oppressive structures that dictate us.

Jordan has just completed an Honours year in Art History, and also completed a Bachelor of Arts with an extended major in Philosophy, and minor in Gender Studies. Their research interests include queer and feminist theory, European philosophy and aesthetics.

ENDNOTES

[i] Georges Didi-Huberman, “Before the Image, Before Time: The Sovereignty of Anachronism” in Compelling Visuality (Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2003), 42.

[ii] Didi-Huberman, “Before the Image, Before Time”, 41.

[iii] Catherine Malabou, Ontology of the Accident: An Essay on Destructive Plasticity, trans. Carolyn Shread (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2012), 6.

[iv] Didi-Huberman, “Before the Image, Before Time”, 36.

[v] Didi-Huberman, “Before the Image, Before Time”, 33.

[vi] Didi-Huberman, “Before the Image, Before Time”, 38.

[vii] Catherine Malabou and Kate Lawless, “The Future of Plasticity” Chiasma 3, no.1 (2016): 104,

https://ojs.lib.uwo.ca/index.php/chiasma/article/view/339.

[viii] Catherine Malabou, What Should We Do with Our Brain? trans. Sebastian Rand (New York: Fordham University Press, 2008), 4.

[ix] Malabou, What Should We Do with Our Brain?, 6.

[x] Malabou and Lawless, “The Future of Plasticity”, 101.

[xi] Catherine Malabou, Ontology of the Accident: An Essay on Destructive Plasticity, 4.

[xii] Simon Bowes, “Dirt in the Lens: On Matter and Memory in Photographic Performance” Performance Research 24, no.6 (2019): 44,

https://doi.org/10.1080/13528165.2019.1686583.

[xiii] Bowes, “Dirt in the Lens”, 43.

[xiv] Nidesh Lawtoo, Homo Mimeticus: A New Theory of Imitation (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2022), 132.

[xv] Ana Horvat, “Tranimacies and Affective Trans Embodiment in Nina Arsenault’s Silicone Diaries and Cassils’s Becoming an Image” Auto/Biography Studies 33, no. 2 (2018): 398,

https://doi.org/10.1080/08989575.2018.1445588.

[xvi] Malabou, What Should We Do with Our Brain?, 11.

[xvii] Malabou, What Should We Do with Our Brain?, 10.

[xviii] Edyta Lorek-Jezinska, “Affective Realities and Conceptual Contradictions of Patricia Piccinini’s Art: Ecofeminist and Disability Studies Perspectives” Text Matters 12, no.12 (2022): 364,

DOI:10.18778/2083-2931.12.22.

[xix] Malabou, Ontology of the Accident, 2.

[xx] Malabou, What Should We Do with Our Brain?, 6.

[xxi] Julia Kristeva, “Approaching Abjection” in The Portable Kristeva, ed. Kelly Oliver (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002), 231.

[xxii] Dino Felluga, Critical Theory: The Key Concepts (New York: Routledge, 2015), 3.

[xxiii] Barbara Creed, Horror And The Monstrous Feminine: An Imaginary Abjection (London: Routledge, 1993), 65.

[xxiv] Malabou, Ontology of the Accident, 3.

[xxv] Nidesh Lawtoo, Homo Mimeticus: A New Theory of Imitation, 132.

[xxvi] Malabou, What Should We Do with Our Brain?, 11.

WORKS CITED

Bowes, Simon. “Dirt in the Lens: On Matter and Memory in Photographic Performance.” Performance Research 24, no. 6 (2019): 38-46.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13528165.2019.1686583.

Creed, Barbara. Horror And The Monstrous Feminine: An Imaginary Abjection. London: Routledge, 1993.

Didi-Huberman, Georges. “Before the Image, Before Time: The Sovereignty of Anachronism” in Compelling Visuality. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2003.

Felluga, Dino. Critical Theory: The Key Concepts. New York: Routledge, 2015.

Horvat, Ana. “Tranimacies and Affective Trans Embodiment in Nina Arsenault’s Silicone Diaries and Cassils’s Becoming an Image.” Auto/Biography Studies 33, no. 2 (2018): 395-415.

https://doi.org/10.1080/08989575.2018.1445588.

Kristeva, Julia. “Approaching Abjection” in The Portable Kristeva. Edited by Kelly Oliver. New York: Columbia University Press, 2002.

Lawtoo, Nidesh. Homo Mimeticus: A New Theory of Imitation. Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2022.

Lorek-Jezinska, Edyta. “Affective Realities and Conceptual Contradictions of Patricia Piccinini’s Art: Ecofeminist and Disability Studies Perspectives” Text Matters 12, no. 12 (2022): 363-379.

DOI:10.18778/2083-2931.12.22.

Malabou, Catherine. Ontology of the Accident: An Essay on Destructive Plasticity. Translated by Carolyn Shread. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2012.

Malabou, Catherine and Lawless, Kate. “The Future of Plasticity” Chiasma 3, no. 1 (2016): 99-108.

https://ojs.lib.uwo.ca/index.php/chiasma/article/view/339.

Malabou, Catherine. What Should We Do with Our Brain? Translated by Sebastian Rand. New York: Fordham University Press, 2008.

Featured photo by Dustin Humes on Unsplash.

1 Comment